Indian Summer, is usually not half as beautiful as the song in its name. And it is often the perfect recipe for mirages, even hallucinations. It is infamous, in the villages and small towns of India, for making people lose sanity.

Everybody I saw on the streets that day, had a white cloth wrapped around their faces. 25 minutes of a tuk-tuk ride, in over 45 degrees celcius temperatures later, I had begun to imagine double barreled rifles slung across their shoulders, as if they were bandits, all of them. The hot wind, or lu, as it is called here, came in gusts, slapping me awake. In my mind, I pictured the train, its cool railing that I found hard to let go of, as I stepped into the hot Gwalior morning.

I could’ve slept all the way to Bhopal. I was tired in my bones. I wanted to be home already, and I had 4 more days of work ahead. The day seemed interminable. It was almost 7:30 in the evening when I wrapped the day’s shoot. My hosts asked me to stay for dinner after work. I needed to shut my eyes until tomorrow. I wasn’t looking forward to the long drive back to the mess, the lime walls still hot from the day’s sun.

I was surprised to see the lights on in my room. Did I leave them on? I couldn’t be sure. There was nobody in, the room was locked. And cool, as if the air conditioner had only just been turned off. A glass of lemonade sat on the side table, the cubes of ice in it, just melting. Could I smell his cologne? No, it couldn’t be. He couldn’t. He shouldn’t be here. He kept insisting that he should come along, even if just for a day. I cursed myself for insisting that he rather not.

I was alone in my room, not a soul around. I walked out into the garden, nobody there either, except the mosquitoes that stung. The caretaker came looking, asked if I’d have dinner. I asked him about the lights, and the lemonade in my room. He answered that he had ‘instructions’, and was told of my tentative schedule.

The dinner with the freshly made phulkas being served to me, cleared my mind a little. I could even laugh at myself and my imagination. Of course he wasn’t here. I had a second helping of the plain vanilla ice-cream before turning in. I’d read a little before I hit the bed.

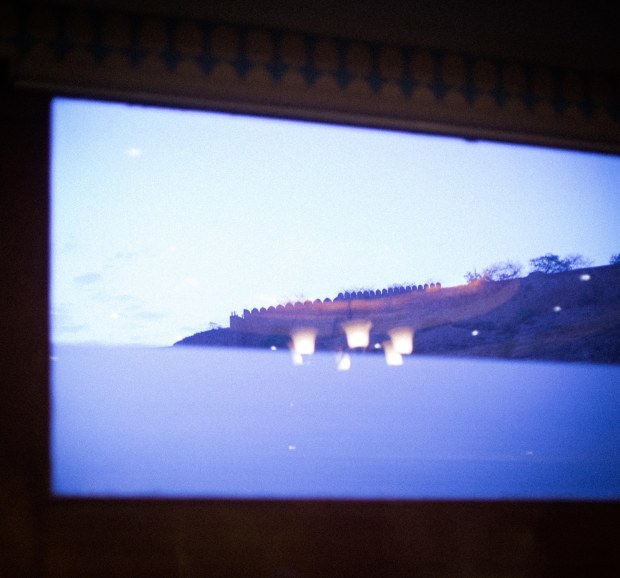

The fort walls looked beautiful, lit, against the inky sky. And Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s ‘Kaee Chaand Thay Sar-e-Aasmaan‘ seemed to compliment the setting. It seemed to be made to be read on such an evening, against the backdrop of such a fort’s walls.

He’d laugh at the romanticism.

And just like that I saw him smiling at me from outside the window. For a second, I froze. And then I ran to the lobby outside. He didn’t come. He wasn’t there in the garden either. The watchman hadn’t seen him, or anyone else. And the caretaker wasn’t even smiling anymore when he said that nobody else was there.

Coming back to my room, I was furious at the tricks my mind was playing at me. I was furious at myself for falling for those tricks. And yet, I could swear that someone had been in my room, just moments ago. The bed was warm where he sat. My book was on the side table now. I had left it on the study table. I hadn’t progressed so far as where the bookmark was now…

“Hai zulf e yaar halqa e zanjeer hoo ba hoo

Rakhti hai aankh sahar si taseer hoo ba hoo…”

I read, and reread the poem attributed to Wazir Khanum. I double and triple checked my room, for him. There was nobody anywhere. Not even at the window. I didn’t realise when I fell asleep. The room was really cold when I woke up, mumbling, clutching his shirt.

I didn’t remember waking up in the night, and taking it from my bag… In fact, I didn’t even remember packing it along with my things, yesterday.

It was impossible to sleep then. The sky was getting lighter, and I felt that a morning walk would be about the right thing to bring me back to my full senses.

The morning breeze was beautiful. And the fort walls looked like gold in the light of the rising sun. I returned to my room, its door ajar, and the caretaker scowling at me, muttering how careless I was. I saw the keys in my hand, and fresh from the walk, I remembered clearly this time, that I had locked the door when I went out. I panicked for my gear, but nothing was missing from my room. Except, his shirt. I looked everywhere for it. It was gone.

I was late getting ready for the shoot. My hosts had sent their car with the chauffeur to save me the trouble of travelling in the heat. I decided to pack my bags and check out as well. The previous night’s events had me out of my depths. I’d ask my hosts for a business hotel closer to the venue.

The chauffeur seemed to be in a hurry to leave there as soon as possible. Driving towards the city, he asked me why I chose to live in that run-down mess when there were so many nicer options available in the city. I told him my friend had made the arrangements for my stay, but I had checked out.

I quickly apprised my hosts about my unnerving experience the previous evening. They looked worried, and asked me about my friend who made the stay arrangements. They were shocked on learning his name.

Capt. Shivendra Singh Chauhan had died of injuries during an encounter with infiltrators near Budgam, last year. In fact, yesterday was exactly one year since his death. Gwalior was his home. Yes, it was him in our picture together…

But it couldn’t be.

I’d taken the picture just before starting for Gwalior. And that was the last day of June, 2014. The time stamp on the picture said March 2013.

It took me all of my will power to focus on the work at hand.

I managed to complete the assignment without disappointing my hosts.

I returned to Delhi, on the verge of a breakdown. It was July, and there was no sign of rain. The night air singed everything it touched. I wanted to ask him what was going on. But he didn’t reach the station to receive me. I was all nerves and I wanted to cry.

I reached home a full hour later. It was quiet like a December night. But I was too tired to feel fear. I opened our cupboard for a change of clothes, and I saw all his clothes were gone. Every one of them. All except a crisp white linen shirt, on a hanger. The one I’d woken up with, in Gwalior.

Φ